- Home

- Jael McHenry

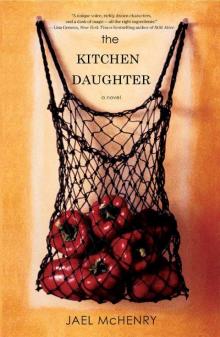

The Kitchen Daughter

The Kitchen Daughter Read online

the

KITCHEN

DAUGHTER

Gallery Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Jael McHenry

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Gallery Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Gallery Books hardcover edition April 2011

GALLERY BOOKS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected]

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Renato Stanisic

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4391-9169-9

ISBN 978-1-4391-9196-5 (ebook)

FOR MY PARENTS,

KARL AND LYNNEA MCHENRY.

ALL THE BEST PARTS OF ME ARE YOU.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Chapter One: Bread Soup

Chapter Two: Shortbread

Chapter Three: The Georgia Peach

Chapter Four: Midnight Cry Brownies

Chapter Five: Omelet

Chapter Six: Mulled Cider

Chapter Seven: Biscuits and Gravy

Chapter Eight: Butternut Squash Soup

Chapter Nine: Hard-boiled Eggs

Chapter Ten: Chicken Soup

Chapter Eleven: Homemade Play-Doh

Chapter Twelve: Hot Chocolate

Chapter Thirteen: Aji de Gallina

Chapter Fourteen: Hot Chocolate

Chapter Fifteen: Ribollita

Acknowledgments

So many generous and wonderful people have contributed to The Kitchen Daughter in countless ways. I could have filled every page of this book with your names. Instead, here is a shorter list of some of my larger debts.

Huge thanks to my brilliant agent Elisabeth Weed and my remarkable editor Lauren McKenna for reading the manuscript that was and recognizing what it could become. I see your patience, diligence, and insight on every page. I’m also immensely grateful to Megan McKeever, Jean Anne Rose, Ayelet Gruenspecht, and everyone else at Gallery Books for their expertise and assistance as I did this whole publication thing for the first time. Many thanks to Kathleen Zrelak, Jenny Meyer, Blair Bryant Nichols, Stephanie Sun, and Samuel Krowchenko for their help with publicity, foreign rights, speaking engagements, and much more. If any of you are reading this without homemade brownies in hand, give me a call and we’ll fix that.

For reading, editing, brainstorming, fact-checking, naming, suggesting, taste-testing, inspiring, advising, and when I needed it, just listening: Michelle Von Euw, Erin Baggett, Heather Brewer, Joan Cadigan and the St. John’s Book Club, Robb Cadigan, Russ Carr, Linda Cambier, Pam Claughton, Keith Cronin, Karen Dionne, Chris Graham, Dan Hornberger, Lynne Griffin, Tracey Kelley, Derek Lee of The Best Food Blog Ever (bestfoodblogever.com), Juli McCarthy, Derek McHenry, Heather McHenry, Randy Susan Meyers, Amy Sue Nathan, Joe Procopio, Kennan Rapp and Rocio Malpica Rapp, Margaret Schaum, Dr. Ariane Schneider, Therese Walsh, and Barbara Yost.

My critique group, for dead-on insight and never-ending encouragement: Ken Kraus, Shelley Nolden, Kelly O’Donnell, Rick Spilman, and Bruce Wood.

My writers’ strategy group, for support and ideas and good company: Camille Noe Pagán, Emma Johnson, Maris Kreizman, Siobhan O’Connor, and Laura Vanderkam.

For writing brilliantly about Asperger’s syndrome, from the outside and the inside: Dr. Tony Attwood, Gavin Bollard, John Elder Robison, and the women from all over the spectrum who contributed to Women From Another Planet?: Our Lives in the Universe of Autism.

Everyone at Backspace (bksp.org), Intrepid Media (intrepidmedia.com), and Writer Unboxed (writerunboxed.com). I’m honored to be a part of some of the best writing communities online. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Friends and family everywhere, from Philadelphia to Petoskey and Westwood to Wasilla, for your love and support. I owe you all more than I can say.

And of course to my husband Jonathan, with whom I share everything, including a brain, and all the credit.

The discovery of a new dish does more for the happiness of mankind than the discovery of a star.

—BRILLAT-SAVARIN

Eat what is cooked; listen to what is said.

—RUSSIAN PROVERB

the

KITCHEN

DAUGHTER

CHAPTER ONE

Bread Soup

Bad things come in threes. My father dies. My mother dies. Then there’s the funeral.

Other people would say these are all the same bad news. For me, they’re different.

The cemetery is the easiest part. There’s a soothing low voice, the caskets are closed, and I can just stand and observe like I’m not there at all. The man in the robe talks (“celebrated surgeon … loving mother …”) and then Amanda does (“a shock to all of us … best parents we could have ever …”). I keep my eyes on the girls, Amanda’s daughters, Shannon and Parker. They’re younger than I was at my first funeral. This, at twenty-six, is my second.

It’s cold. They must have heated the ground to dig the graves. The soil wouldn’t yield to a shovel otherwise. Not in December, not in Philadelphia. I know that from the garden.

After Amanda finishes talking, she walks back toward us and leans against her husband. She makes a choking sound and I can see Brennan’s arm reaching out to hold her. She bends her head down, leaning further in, until she’s almost hidden. Held in Brennan’s other arm, Parker drops a Cheerio and makes a little O shape with her tiny mouth. Dismay, surprise, something. I hope she doesn’t start crying. Everyone is crying but me and the girls. They don’t because they’re too young. I don’t because I don’t feel like this is really happening.

A new voice, a man’s voice, goes on. I don’t listen to the words. It doesn’t feel real, this funeral. It doesn’t feel like I’m here. Maybe that’s a good thing. Here is not somewhere I want to be. Dad’s gone. Ma’s gone. I’m not ready.

I look at hands clutching tissues. I watch feet shifting back and forth on the uneven ground. All the toes point in the same direction until, by a signal I miss, they don’t. I walk slowly so I don’t trip. Amanda reaches back and gestures. I follow her to the car. We travel back home by an unfamiliar road. I stare down at my black skirt, dusted with white cat hair, and feel the pinch of my narrow black shoes.

But at home, things are worse. There isn’t even a moment for me to be alone before the house fills up. Strangers are here. Disrupting my patterns. Breathing my air. I’m not just bad at crowds, crowds are bad at me. If it were an ordinary day, if things were right and not wrong, I’d be sitting down with my laptop to read Kitcherati, but my laptop is up in my attic room on the third floor. There are too many bodies between me and the banister and I can’t escape upstairs. This is my only home and I know every inch of it, but right now it is invaded. If I look up I’ll see th

eir faces so instead I look down and see all their feet. Their shoes are black like licorice or brown like brisket, tracking in the winter slush and salt from the graveyard and the street. Dozens.

Without meaning to listen, I still hear certain things. I catch Isn’t she the older one? and Not standing up for the people who raised you right, I just can’t say and Strange enough when she was a girl but now it’s downright weird and Caroline always did spoil her something awful. I keep moving around to escape attention, but these conversations fall silent around me, and that’s how I know it’s me they mean. When people aim their condolences at me, I say “Thank you,” and count to three, and move away. Once I find myself in a corner and can’t move but Amanda comes to move the other person instead. I feel rescued.

It gets warmer, worse, like they’re not just inside the house, they’re inside my body. Stomping around on the lining of my stomach. Swinging from my ribs. They’re touching everything in the house, pale fingers like nocturnal worms swarming over picture frames and the doorknobs and the furniture, and if they get to me they’ll crawl and cluster all over my skin.

I look up, away, searching for something reassuring. These things are the same as ever, I tell myself. These things have not changed. The ornate plaster molding, a foot-wide tangle of branching, swirling shapes, lines the wide white ceiling. Tall doors stretch up twice as tall as the people, twelve thirteen fourteen feet high. There’s plenty of room, up there. It’s my home. These are its bones. Good bones.

Then I feel warm breath and someone’s solid bread-dough bulk, only a couple of feet away. It’s one of the great-aunts. I recognize the moles on her throat. She says, “I’m so sorry, Ginevra. You must miss them terribly.”

Her hand is close to my arm. My options are limited. I can’t run away. I can’t handle this.

I lose myself in food.

The rich, wet texture of melting chocolate. The way good aged goat cheese coats your tongue. The silky feel of pasta dough when it’s been pressed and rested just enough. How the scent of onions changes, over an hour, from raw to mellow, sharp to sweet, and all that even without tasting. The simplest magic: how heat transforms.

The great-aunt says, “You miss them, don’t you?”

I want to respond to her question, I know that’s the polite thing to do, but I don’t know what to say. It’s only been three days. Missing them won’t bring them back. And what difference does it, would it, make? I haven’t seen this woman since I was six. I’m not likely to see her again for years. What’s it to her, how I feel?

In my mind, I am standing over a silver skillet of onions as they caramelize. The warmth I feel is the warmth of the stove. I’ve already salted the onions and they are giving up their shape, concentrating their flavor. In my imaginary hand I have a wooden spoon, ready to stir.

“Ginevra, dear?” the great-aunt says.

“Auntie Connie,” interrupts Amanda’s voice. “Thank you so much for coming.”

Connie says, “Your sister seems distraught.”

I nod. Distraught. Yes.

Amanda says, “Ginny’s having a tough time. We all are.”

I see her hand resting on Connie’s shoulder, cupped over the curve of it, her fingers tight. I peek at Amanda’s face and her eyes are still red and painful-looking from the tears. I wish I could comfort her. I concentrate on her familiar gold ring. It’s the color of onion skin. Yellow onions aren’t really yellow, it’s just what they’re called. Just like dinosaur kale isn’t made from dinosaurs and blood oranges don’t bleed.

“It’s a shame what happened. Terrible shame. You should sue,” Connie says.

“We’re thinking about it,” says Amanda.

“They were so young,” says Connie.

I say, “They weren’t that young,” because they weren’t. Dad was sixty-five. Ma just turned fifty-nine. We had her birthday two weeks ago, right before they left. She made her own cake. She always did. Red velvet.

“We miss them something awful,” says Amanda, not to me. Her voice is unsteady. “We’re so glad you and Uncle Rick could come, Connie. Do you want to come meet your great-nieces?”

“Oh, yes please, we don’t get up here very often anymore,” says Connie. She lets herself be ushered away. But in the next moment there’s another someone coming toward me and I just can’t stand this, all these shoes, all these bodies. There are only so many times my sister can rescue me. Two, three, five—have I used them up already?

Crowding my right shoulder is a man with no hair, his head as pale and moist as a chicken breast. His breath smells like bean water.

“Ginny of the bright blue eyes! The last time I saw you you were so small! So small! Like this!” he exclaims, gesturing, his hand parallel to the floor.

“Got bigger,” I mumble. I have to escape somehow, so I excuse myself without excusing myself and head for the kitchen. Five steps, six, seven, praying no one follows me. When I get there, I’m still shaken. I pull the folding doors closed.

Breathe. This is home, and it feels like home. All rectangles and squares. The kitchen is a great big white cube like a piece of Ma’s Corningware. Tall white cupboards, some wood, some glass, stretch up toward the long leaded glass rectangles of the skylight. Next to the fridge we have a step stool because only Dad is tall enough to reach the top shelf of the cupboards without it. One whole wall is lined with shelves of cookbooks, bright rectangles of color sealed behind glass-paned doors, which protect them from kitchen air. Ma’s books on the left, mine on the right. A floor of black-and-white square tiles stretches out toward the far wall, where there’s a deep flat sink, itself made up of rectangles. The wide white counters are rectangles, and so are the gray subway tiles of the backsplash above them. In the center is Ma’s butcher block, which was once her own mother’s, a rectangular wooden column with a slight curve worn down into the middle over the years. The single square window has an herb garden on its sill, four square pots in a row: chives, mint, rosemary, thyme. Any wall not covered with bookshelves or cupboards is rectangular brick. Other people call it exposed brick but I don’t. It is painted over white, not exposed at all.

I kick off my shoes and feel cool tile under my bare feet. Better.

The hum of strange voices creeps in through the folding doors. I imagine Dad at the stove in his scrubs, shoulders rounded, hunched over and stirring a pot of Nonna’s bread soup. He is so tall. I take the hum of the strangers’ voices and try to shift it, change it into a song he’s humming under his breath while he stirs.

All those people. All those shoes. I need to block out their bulk, their nearness, their noise.

Nonna’s books are on my side of the cabinet, which is alphabetized. I reach down to the lowest shelf for a worn gray spine labeled Tuscan Treasures.

When I open it a handwritten recipe card falls out. At the top of the card Best Ribollita is written in loose, spooled handwriting. I never learned Italian. The first time I knew that bread soup and ribollita were the same thing was at her funeral. I looked it up afterward in the dictionary. It was on the same page as ribbon and rice and rickshaw.

My heart is still beating too fast. I dive inside the recipe and let it absorb me. I let the instructions take me over, step by step by step, until the hum begins to fade to silence.

I draw the knife from the block, wary of its edge, and lay it down next to the cutting board while I gather the garlic and onion. The garlic only has to be crushed with the broad side of the knife and peeled. I lay the blade flat on top of the garlic clove and bring down my fist. It makes a satisfying crunch.

The onion has more of a trick to it. Carefully, slowly, I slice the onion through the middle to make a flat side and slip my thumb under the dry gold-brown peel, exposing the smooth whiteness underneath. I lay half the bare onion flat on the cutting board and use the tip of the knife to nip off the top and the root end. I curl my fingers underneath to keep them away from the blade. The recipe says “coarsely chopped,” so I cut thick slices, then hold the

sliced onion back together while I cut again in the other direction. I take my time. The knife snicks quietly against the cutting board. The sound relaxes me. There’s a rhythm to this. Onion and garlic in the pot. Sizzle them in oil. Check the instructions again.

Gather and open cans. Drain the can of beans, rinse them. The recipe calls for canned tomatoes broken up by hand, so I hold each one over the pot and push through the soft flesh with my thumb, squirting juice out, before tearing the tomato into chunks. The juice in the can is cold from the cabinet. Ripping up the tomatoes makes my fingers feel grainy. Something, maybe the acid, irritates my skin. I rinse my hands and dry them on the white towel that hangs next to the sink.

Wash and dry the kale, slice out each rib, cut the leaves in thin ribbons. Drop. Stir. Square off cubes of bread from a peasant loaf, football shaped. Cubes from a curved loaf, there’s a trick to that, but I do my best. Everything goes in. I thought I remembered cheese, but when I double-check the recipe, it’s not there. Salt, pepper. I adjust the heat to bring the soup down from an energetic boil to a bare simmer. That’s the last of the instructions. The spicy, creamy, comforting scent of ribollita drifts upward. I breathe it in.

I’m opening the silverware drawer for a spoon when I notice her.

On the step stool in the corner of the kitchen, next to the refrigerator, sits Nonna. She is wearing a bright yellow Shaker sweater and acid-washed jeans.

Nonna has been dead for twenty years.

Nonetheless, she’s right there. Wearing what she wore and looking how she looked in 1991.

In my grief, I am hallucinating. I must be.

She says, “Hello, uccellina.”

The name she had for me, Little Bird, from the mouth that spoke it. I am hallucinating the voice as well. Low, sharp, familiar. The first time I tasted espresso I thought, This is what Nonna sounded like. This is her. The whole Nonna, solid. Right here, sitting in the kitchen.

The Kitchen Daughter

The Kitchen Daughter